On my recent trip throughout Europe, I met communists in just about every country I visited. Some were expected, pre-planned encounters, and others, like the Vietnamese communist who worked at an overnight convenience store in Prague, were pleasant surprises. In Luxembourg, I talked with the chairman of the KPL, who told me about their robust weekly publication and their work to court community support. In Ireland, I happened to be there in the lead-up to the European elections and saw a Trotskyist party running a candidate. I went to Connolly Books, chatted with a worker, and picked up some literature.

Needless to say, everywhere I went communism was a binding agent that connected me with seemingly unrelated people. This kind of international solidary has a long and sometimes troubled history, dating from the first iterations of internationalism in Marx and Engels’ writing, to the collapse of internationalism during the First World War, its re-emergence with the Communist International (Comintern), and finally, today’s association of ‘internationalism’ with so-called “Trotskyism.”

In this essay, I want to briefly outline that complicated history and suggest the need for a new kind of internationalism premised on the socio-economic interconnectedness that defines our age more than any before it. If Vijay Prashad and others are correct in their assessment of today’s present kinetic imperialism as “hyper imperialism” then we also need to update our notion of internationalism. In doing so, I want to move away from the anachronistic Trotskyist notion of “internationalism,” or “permanent revolution” (although I do think some of his points here are useful) and recast the terms of our increasingly globalized and economically dependent world.

It also suggests putting some kind of harness on the emergence of Patriotic Socialism, which, although it must be taken seriously, threatens to obfuscate the internationalist elements that are integral to any future revolutionary transformation. I do not believe that internationalism is incompatible with patriotic socialism, but I do believe that the two trends need to be reconciled with recent global developments, including the universality of climate change, credit, the internet, and globalized and computed corporate finance. Nothing demonstrates this more than the recent IT outage that paralyzed global airlines, businesses, and broadcasts.

I believe that part of the reason internationalism has been so categorically rejected since the mid-twentieth century has to do with Joseph Stalin’s advocacy and exportation of the “Socialism in One Country” theory, which corrected some of the misgivings of Bolshevik leaders who believed thoroughly in the coming world revolution. As we will see, Lenin, Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev, and Kollontai, among others, were not wrong in believing that they were approaching a global collapse of capitalism, but they underestimated both capitalism’s corrective abilities and the effect that de-colonization would have as a mechanism to extend, rather than restrict, the market.

Yet, one thing we must keep in mind about Stalin’s theory of socialism in one country, is that it was a response to the failure of international revolution to materialize, not an imbedded theoretical component of Marxism. Stalin argued, “It is no use building Socialism without being sure that we can build it, without being sure that the technical backwardness of our country is not an insuperable obstacle to the building of complete Socialist society.” Stalin worked out the theory over time and in response to leaders like Zinoviev who maintained the belief that socialist revolution had to be international to be transformative.

Stalin came to power at a time when the world’s major industrial powers entered a period of prolonged retreat and insularity. Take, for example, the United States after World War One. In 1920 Warren Harding won the presidential election on the promise of staying out of global affairs. Not only did the United States fail to ratify the Versailles Treaty and enter the League of Nations, but it also imposed high tariffs on imported goods to protect American manufacturing. The Jonson-Reed Act of 1924 limited immigration into the USA and set quotas for immigrants coming from northern and western Europe. Britain, France, and other European allies followed, insulating their economies and retreating from the globalizing push of the late nineteenth century. Some historians argue that American and British isolationism is responsible for the second world war in the way they limited foreign trade and the extension of credit, giving countries like Italy, Germany, and others no other option but to expand their markets through old-fashioned imperialism.

Keeping that history in mind, we can dive deeper into the changing quality and purpose of internationalism. My basic argument here is that if we follow historical manifestations of internationalism, we see that it responded specifically to conditions arising at the time, from the rise and fall of global capital, conflict, and socio-economic change. Since the collapse of the Third International and the fall of the Soviet Union, internationalism has failed to re-cast itself as anything other than a Trotskyist hold-over, but the age of global finance capital, technology, and ‘hyper-imperialism’ necessitates a new approach to international solidarity and collaboration. Social media, communications, and efficient modes of transportation offer possibilities for international cooperation like never before.

A Brief History of Communist Internationalism

The Marxist theory of internationalism is premised on the notion that workers are inherently nationless. In 1864 Marx helped create the International Workingman’s Association to give voice to the international working class (meaning at this time mostly just Europe). In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels claimed that “The workers have no fatherland” meaning that the nation-state, as a bourgeois construct stands as a vital arena for the struggle between the classes but does not serve as the natural state for workers. They declared that “the struggle of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie is at first, in form though not in content, national in character. The proletariat must first settle accounts with its own bourgeoisie.” Thus, the two grandfathers of scientific socialism promoted a rather ambiguous notion of the dialectic struggle: the structures of the old bourgeois nation-state provided the grounds for what would become a new international worker’s state.

Marx recognized in his own time that the evolving nature of capitalism changed the conditions of the nation. The nation-state, as articulated in the French Revolutionary period, was a “weapon of the rising social order in its struggle for emancipation.” Industrial capitalism—the next stage—threatened to break the bonds of the nation in its quest for raw materials and markets, creating an interdependence of nations. Marx, ever foresighted, described how capitalism moved to homogenize the world and obliterate national particularities. Thus, the threat to their national identity with the ascendance of capitalism meant for Marx that “the struggle of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie is at first, in form though not in content, national in character.” Workers were thus simultaneously without a fatherland but forced to work out their emancipation within the nation-state paradigm.

To foster solidarity across national boundaries, some of the earliest working-class advocates created the First International Workmen’s Association or the First International. Marx participated in its founding but remained relatively obscure until his Address to the Working Classes.

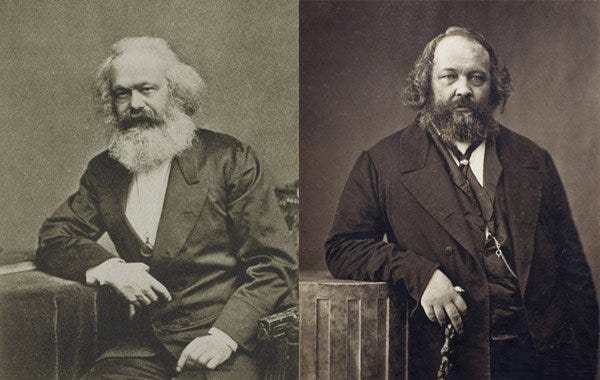

The first international did not last long owing to tensions between the mutualists who supported anarchistic notions of the state and opposed communism. The Russian Anarchist Mikhail Bakunin further divided the body between competing views of revolution. Simply put, Bakunin and his supporters advocated for a complete economic struggle against capitalism and an overthrowing of the state without participating in parliamentarianism. Marx, on the other hand, argued for parliamentary activity under the notion that a revolutionary situation and regime must emerge from the pre-existing conditions and institutions.

The debate reached a fever pitch at the fifth congress in The Hauge, Netherlands, where Bakunin blamed Marx for being and promoting an authoritarian doctrine. Marx fired back by saying that Bakunin lacked comprehensive theory, failed to understand the class struggle, and naively approached the question of the State. The communists attempted to expel Bakunin and his ilk, but the First International proved incapable of staying together after its split.

In 1889, soon after Germany’s Anti-Socialist laws were lifted, socialists across Europe led the initiative to create the Second International, this time excluding anarcho-syndicalists.

Europe had been teetering for decades toward a major calamity. To unify Germany, the first Minister President, and then Chancellor of the newly united Germany went to war with Denmark (1864), Austria (1866), and France (1870). The Paris Commune, or Civil War, raged in 1871, and Russia went to war with the Ottoman Empire in Southeastern Europe from 1877-78. These are just European wars and exclude the numerous colonial wars European powers waged in Africa, Asia, and South America.

Witnessing the devastating march of European Imperialism, the Second International committed itself to working out a compressive socialist response and position on war and militarism as a way of demonstrating solidarity among the world’s working class against the blood lust of the European bourgeoisie.

At the Second International’s Stuttgart Congress in 1907, delegates from around the world debated the theme “Militarism and the National Conflict.” Gustave Hervé and the extreme left called for an insurrectionary response in the moment of war, Jules Guesde argued that any antiwar actions were futile under capitalism, and Jean Jaurès took the middle ground by arguing that general strikes, petitions, and any means must be exercised to avoid war. Lenin, Martov, and Luxembourg added an amendment that stipulated that if a war does break out, socialist parties must “intervene in favor of its speedy termination” and “do all in their power to utilize the economic and political crisis caused by the war to rouse the people and thereby hasten the abolition of capitalist class rule.”

Hence, the Second International took a definite anti-war position that placed national priorities to the side of international solidarity. Yet, when World War One broke out, many participating parties found themselves in a bind. Germany, as de facto head of the Axis powers, is the greatest example. When the war began the Social Democratic Party had a large number of delegates in the Reichstag, and yet with the declaration of war, the Kaiser needed war credits. Conservative and liberal parties promoted the war as a national cause for the preservation of German power and influence, and they managed to convince many workers and unions of the cause. The German socialists thus confronted a dilemma: vote against war credits and lose the support of the vast majority of workers or vote in favor of war credits and (potentially) retain their electoral influence. On August 4th they chose to vote in favor of the war, and many socialist parties in Europe followed, belying the strategy and virtually collapsing the Second International.

During the war, the more radical socialists maintained their anti-war position and saw the conflict as an opportunity for revolution. The so-called Zimmerwald Left, named such because of their meeting in Zimmerwald, Switzerland convened in 1915 to work out a new consensus on how to approach the war. The debate centered around Karl Liebknecht and Lenin’s theory of “defeatism” which stressed the need of their countries to lose the war to discredit the regime and foment revolution and civil war. The other option, advocated by the moderate wing of the conference and those who had voted for the war, including Karl Kautsky, called for continued advocacy for peace.

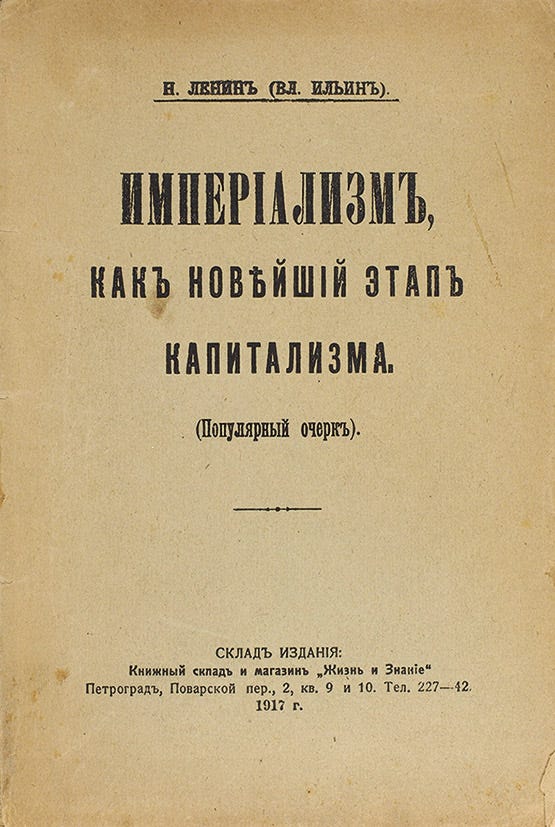

It was also within this context that Lenin wrote “Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism,” which reflected on the growth of monopolies and the increasing danger of war between competing national/financial interests. In other words, the competitive struggle for markets and raw materials led to a crisis in the capitalist world system that only war and revolution could overcome.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Alex’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.