Part I: Marxism, Liberalism, and “The Women’s Question”

A Historical View and Distinction of Marxist Feminism

Part I of II

“It is noteworthy that the efforts [for full equality of the sexes] here roughly sketched, do not reach beyond the framework of the existing social order. The question never is put whether, these objects being attained, any real and thoroughgoing improvement in the condition of women will have been achieved. Standing on the ground of bourgeois, that is, of the capitalist social order, the full social equality of man and woman is considered the solution to the question. These folks are not aware, or they slide over the fact that, in so far as the unrestricted admission of women to industrial occupations is concerned, the object has already been actually attained, and it meets with the strongest support on the part of the ruling class, who…find therein their own interest. Under existing conditions, the admission of women to all industrial occupations can have for its only effect that the competitive struggle of the working people become ever sharper, and rage ever more fiercely. Hence the inevitable result–the lowering of incomes for female and male labor, whether this income be in the form of wage or salary.”

This passage, written by German Social Democrat August Bebel in 1904 perfectly encapsulates the main difference between liberal feminism and socialist feminism. On the one hand, it's no surprise that Bebel, a man, confronted what was known at the time as “the woman’s question” in conservative, liberal, and radical circles. The woman’s question concerned the present and future role of women in politics and society, and whether they contribute to emerging liberal democracies of the twentieth century. Bebel agreed with the core aspiration for equality between the sexes, but, as he indicates here, the systemic cause of inequality is rooted deeper than simple “emancipation.” For Bebel and many others, the challenge was simple: liberal lawmakers willingly acquiesced to expanding women’s rights so long as it empowered a new labor force and mobilized a more liberal-conservative voting base to undermine the emergence of socialism. In other words, giving women the right to vote was thought to be a way of diluting the socialist threat. The real solution, Bebel argued, was not to be found in laws proclaiming equality, but the full-scale eradication of capitalist social relations.

The tension between liberal feminism and socialist feminism, largely ignored in the past 30 years, is re-emerging as of late because people feel like the feminism pushed through major political characters like Hillary Clinton and Kamala Harris does not relate to their own experience. As a new virulent form of identity politics takes hold of radical spaces, entire friendships have broken, huge blowouts have occurred, and accusations of “sexism” abound. We’re not talking about someone being canceled, we’re talking about the consequences of two conflicting interpretations of feminism under a common “leftist” umbrella: one, which is most commonly taught and more easily understood, and another, which requires independent and in-depth study to comprehend. Sure, there are other forms of feminism, but for the revolutionary left only two concern us today– liberal feminism and all its guises and Marxist feminism (also referred to as materialist feminism).

As socialist activists and theorists, we’ve often found ourselves in situations where our friends and ‘allies’ question our feminist credentials or the type of liberation we seek for women. Part of the reason stems from a failure to understand the difference between liberalism and leftism (particularly in the United States, where the former president purposefully conflates the two). Even within ‘leftism,’ anarchism and progressivism advocate a type of feminist theory devoid of real class analysis that is more in line with liberal individualism than socialist collectivism. Another reason for the misunderstanding is the simple fact that liberal feminism benefits from being the oldest tradition, as the struggle for things like suffrage, equal pay, and equal rights aspire to equalize the sexes within a system that depends on individualist ideology. The assumption has been that “womanhood” alone constitutes a “community,” even though most people are willing to admit that the economic interests of women in the 1% are vastly different than those in the 99%.

Most importantly, feminism is closely guarded and monitored because certain experiences form the basis of the female experience under liberal capitalism, and these experiences are personal and emotional. For example, most men do not realize that women frequently code-switch when talking to men, particularly in professional settings where masculine expectations abound. More horrifyingly, some polls suggest that at least 97% of women in the United States have experienced some form of sexual assault, versus just 1 out of 33 men. That’s as good of a reason as any to want to be sure that the men in your life support the feminist cause. However, the problem emerges when the feminism that you expect out of your friends might be different than the feminism that underscores their worldview.

In this two-part article, we go through the history of feminism to demonstrate both the diversity of feminist thought and to account for the dominance of liberal feminist ideology today. First, we explore the earliest manifestations of an organized feminist movement, preceding the First World War but culminating in the achievement of broad-based suffrage in the West. Second, we turn to the post-war turn toward both queer feminism and radical feminism, two powerful offshoots that have both diversified the cause and restricted it in many ways. Finally, after establishing and presenting our understanding of liberal feminist history and theory, we present socialist/materialist feminism, not as something new, but as an older tradition that had been largely marginalized after 1955, when the Soviet Union repealed the right to an abortion. We benchmark that date because, upon their seizure of power, the Bolsheviks largely turned socialist feminist theory into practice through the first Family Code in 1918 (giving women the right to divorce), legalizing abortions (1920), the outlawing of marital rape (1922), and the conference of equal rights and equal pay, all overseen by a special “women’s department” within the government. Despite the later repeal of abortion, the early Bolshevik state vastly expanded women’s rights, but the repeal gave liberal feminists ammunition to second-guess the Soviet Union’s feminist advances. The argument that we want to put forward is that the exclusion of materialist views on feminism and women’s liberation is dangerous in that it threatens the broader project for women’s liberation and alienates committed and militant activists who are materialists. Our main concern is that sometimes it is hard to identify yourself as a feminist because a lot of self-identified feminists stop short of aligning with our struggle against capitalism in a fundamental sense.

From the Suffragettes to “Girl Boss”

The bicycle, a seemingly innocuous instrument for individual travel, was one of the primary symbols of female liberation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries because it represented a woman’s right to independent physical mobility. As capital expanded to every corner of the globe, and finance capital from the industrial metropole spread to new parts of the world, factories and workshops in Europe and North America had to expand the workforce. Women, constituting at least half of the population, provided such an untapped source of labor, and with their increased employment came increased demands for political representation through full suffrage within the supposed liberal democratic policies that claimed to protect them. Their primary mode of transportation to and from work? The bicycle– a two-wheeled ticket to the right to work.

To be sure, the suffrage movement existed well before the late nineteenth century, with the first Women’s Rights Convention in 1848 usually hailed as the beginning of the first major social movement. 1848 was a monumental year for Europe, commonly referred to as the “Springtime of Europe,” where radical, liberal, and conservative social movements exploded onto the political scene across the continent convening constitutional conventions, vying for new nationally-based governments, and challenging the power of the remaining aristocracy. Despite the breadth of activism in 1848, most historians see the revolutions as failures, as one by one conservative counter-revolutionary forces squashed rebellions and reconstituted power. For women’s liberation, 1848 was a give-and-take. On the one hand, the Convention clearly articulated the first goals of the women’s suffrage movement, but the promises of the liberal revolutions never achieved enough to open the opportunity to realize social transformation.

The convention largely adopted the goals of its predecessors. People like Olympes de Gouges who wrote the “Declaration of the Rights of Women and the Female Citizen” in 1791, and those involved in the temperance movement, founded in Boston, were terrorized by the role that alcoholism wrought on their household. By 1848, a plethora of causes highlighted the need for a broad-based movement of women’s liberation, struggling for equality before the law as equals to not only men but also African Americans and other minority groups. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, the call for women’s liberation paired well with the social issues arising from social inequality, racism, and colonialism.

The problem was, however, that men still dominated many of the abolitionist and temperance movements, which led women like Lucretia Scott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton to create the Women’s Rights Convention, setting the stage for a basic liberal feminist position. The declaration that came out of the convention put forward the argument that men and women are created equal and that women have an equal right to education, private property, and suffrage.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, women fought hard for the basic civil rights laid out in the Declaration. By the First World War, as men ventured to the battlefield, companies looked to hire women as the latent domestic workforce, furthering the call for equal participation in government. The First World War can be cited as the beginning of a real Marxist feminist movement because along with Bebel, (mentioned in the introduction), socialists like Rosa Luxembourg, Clara Zetkin, or Alexandra Kollontai advocated on behalf of working-class women throughout Europe. As in most social causes, communists lead the charge, with Luxembourg arguing, for example, that “The bourgeois woman has no real interest in political rights because she exercises no economic function in society, because she enjoys the ready-made fruits of class domination. The demand for women’s rights, as raised by bourgeois women, is pure ideology held by a few weak groups without material roots, a phantom on the antagonism between men and women, a fad.”

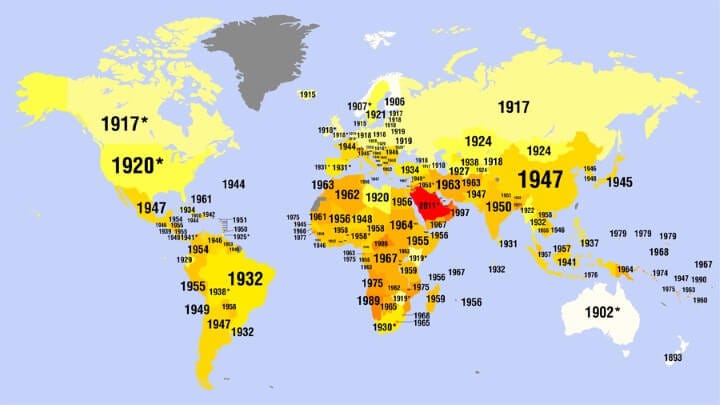

By the 1920s, with the advances of the new Soviet Union, central and northern Europe granted women suffrage, and in 1920 the United States approved the 19th Amendment. Liberal governments at the time assumed that if they granted women the right to vote, they could count on the lasting support of women in the ballot box. However, it soon became apparent that even though women could cast their vote, they remained largely excluded from high political positions or even trade unions and were still subject to disproportionate wages, professional representation, and social benefits, all compounded by the persistent “double burden” of having to work full time while maintaining domestic affairs.

The problem, as many feminists understood it, was that even though women could vote, they still occupied a position as “second class” citizens, closer in social position to minorities than to men. The contradiction was most vivid in the United States, where the Civil Rights movement renewed interest in the fight for fair representation as a broad-based coalition. People like Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan paired their struggle (sometimes referred to as the “second wave”) with black liberation, carrying the mantra “After black power, women’s liberation.” The pairing of the two social issues outlined the contours of mid to late-twentieth-century feminism, which focused on women’s empowerment through representation, climbing social ladders, and equal opportunity to professional positions through hard work.

The largely middle-class, heterosexual movement, dominated by white women seeking equality in representation, focused on the individual freedom to choose, implying that every choice a woman made was inherently feminist because it was made by a woman. This was a type of feminism that paired well with the so-called ‘American dream’ and the emerging Washington Consensus, where hard work, austerity, and dedication produced social mobility and capital success. Initiatives like “Bring Your Daughter to Work Day” sought to inculcate young girls with the promise of unfettered social mobility. The advocacy coalesced around empowerment over liberation in the sense that the goal was not the eradication of social and economic structures that oppressed women, but rather taking control of the existing structures for the reformist goal of dismantling institutional patriarchy as a stand-alone issue, unrelated to the scaffolding of capitalism.

The war on patriarchy implied that capitalism was a safe platform to lead the fight, and by the 1990s, especially after the Monica Lewinsky scandal, feminist activism entered a realm of commodification heretofore unseen. Numerous articles have been written about the rise of female-oriented marketing campaigns in the 90s, so suffice it to say that corporations learned that a particular form of empowerment sells. With increased purchasing power in the major industrialized countries of the West, companies targeted domestic product ads for things like detergent, soaps, hygienic products, and children’s toys to women and mothers. Truthfully, there was nothing new about the appeal to women, but the ads of the 1990s used female empowerment in a way that those of previous decades could not.

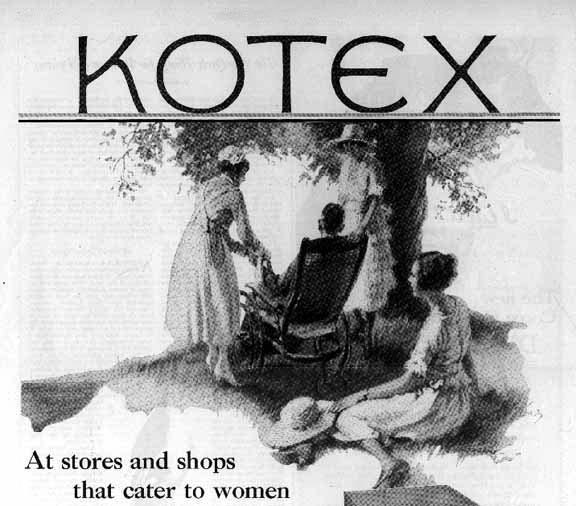

For example, compare the two ads below. In the Kotex one from the 1920s, feminine menstrual products are pitched as an aid to maintaining an everyday routine, with two women catering freely to a man on a chair, and another woman sitting, enjoying the outside. We don’t know which woman is menstruating, because the point of the product was to suppress the public perception of menstruation.

The second ad is strikingly different. The brand name “always” is an easily recognizable sign for feminine hygiene products, but the insignia hardly matters. Most prominent in the ad is a forefronted girl, gripping a baseball as if to pitch (often considered a “male” game). There is nobody else in the ad obscuring our understanding of who needs hygiene products because menstruation is no longer something that needs to be kept secret.

The campaign to sell women's products using empowering imagery, co-opting traditional “male” stereotypes, and circulating catchphrases became so successful that the “new woman” seemed (seems) inseparable from the fully commodified female– ‘homo kapitalismus.’ Taken to its most extreme, the ‘trad wife’ (she who gladly fulfills domestic duties without complaint) embodies the most logical conclusion of classical liberal feminism in that the “choice” to submit to domestic duty is considered “empowering.” In other words, the most perverse form of liberal feminism can argue that a woman's choice can turn a subservient social role into an acceptable or desirable one so long as it's consensual.

In the second half of this article, we explore the development of radical feminism and queer feminism before diving into Marxist feminism. It's important to point out that we do not see these traditions existing in strict sequential order–they continue to develop alongside each other, co-existing as symbiotic traditions sometimes at odds and sometimes complementing each other.