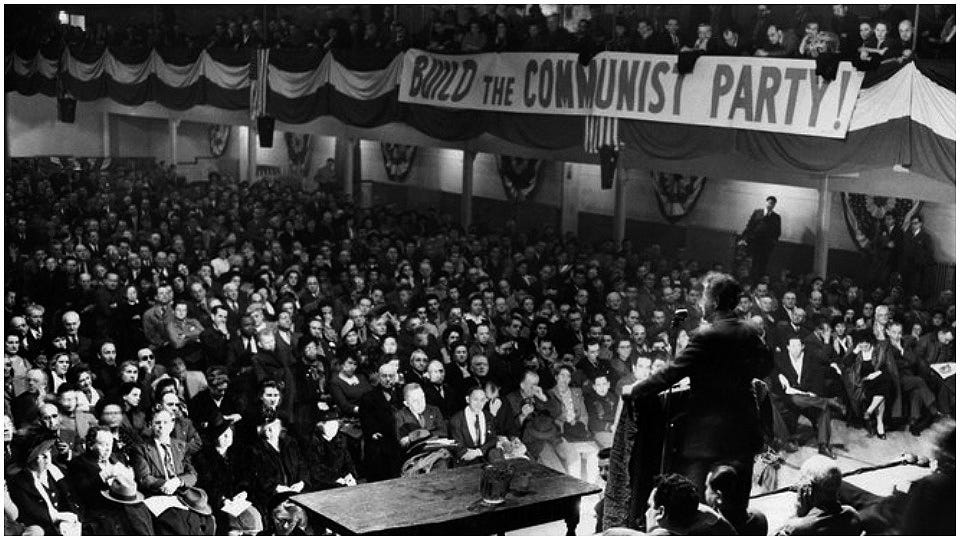

American communism has always been plagued by factionalism. After the mass arrests and the Palmer raids following the Russian Revolution of 1917 subsided, American communists re-emerged from underground work in the 1920s to reconstitute themselves behind the support of Moscow’s mighty Communist Third International (Comintern). The problem, however, was that American communism was fractured into two predominant camps: the Communist Labor Party (CLP), and the Communist Party (CP), among others. Both factions worked tirelessly against the reformist Socialist Party of America for their over-reliance on electioneering, and both parties ultimately adhered to the Comintern, but their similarities ended there. To simplify the dispute, the CLP believed in participating in elections to root itself in American life, while the CP, favored by Moscow, believed that over-reliance on the electrical struggle would contaminate the ultimate commitment to revolution. The dispute seems ephemeral now, but at the time it played a major role in prohibiting communist unity. In fact, the dispute became so endemic that it led many to leave the communist movement in frustration over lethargy—a problem not only for American communist but for Moscow’s internationalist aspirations.

What the Comintern understood about American communism was that individualism was hardwired into the American psyche more than any other country. For a country that—as Fredrick Jackson Turner pointed out at the end of the 19th century— built itself on the promise of private property and rugged individualism, the task of inflecting a collectivist spirit seemed nearly impossible. Indeed, that individualism was at the root of party factionalism, for while the American communists hailed the benefits of democratic centralism they failed to live up to it in practice.

In 1921 the Comintern drew up a document on “the Next Tasks of the Communist Party in America,” which ordered the creation of a legal united party. It argued that Americans would be kicked out of the Third International if they could not come together to overcome their differences. The new Communist Unity Party that it called for was to have a mild domestic platform calling for immediate reforms while maintaining the long-term goal of revolution. Moscow’s commitment to ending American factionalism reflects its frustration over the collapse of international revolution. As Lenin wrote to American workers, “We know that your aid, American working comrades, will perhaps not as yet come quickly at all, as the Revolution proceeds in different forms and in varying tempo in the various countries (and it cannot be otherwise).” Above all, the Comintern understood that the differing approach to means should not be a justification for sacrificing the common end goal.

Still, Gregori Zinoviev, then chairman of the Comintern, recognized something idiosyncratic about American communism when he sent a special communication to the central committees of the two factional parties stating that their split “rendered a heavy blow to the Communist movement in America.” He went on to point out that “Insofar as both parties stand on the platform of the Communist International—and of this we have not the slightest doubt—a united party is not only possible but is absolutely necessary, and the [Comintern] categorically insists on this immediately being brought about.” Zinoviev’s attempt to push for a United Party signaled Moscow’s larger goal to centralize decision making, echoing Lenin’s address to the 10th Party Congress in 1921 on Party Unity. Factions undermined the goal of international communism, opened the door to opportunism, belied the strategy of democratic centralism, and ultimately stalled the struggle.

All Marxists worth their salt know the famous quote that history repeats itself, first as tragedy, and second as farce. I bring up this early history of American communism in order to raise certain points relevant to today. We socialists and communists are at the precipice of a major breakthrough, but I worry that the continued factionalism will render our moment a tragedy more than a triumph. The Comintern no longer exists to demand that we reconcile our differences, and the Soviet Union no longer exists to provide a standard of democratic centralism. America lacks an institutionalized Labour Party, and China has never willingly acted as an arbiter of foreign communist differences. We are left in the heart of global imperialism as a collection of trees—each a variety of maple—fractured so as to allow sunlight through and at high risk of being felled. We need to close the gap to somehow render a forest from the desperate trees. This is not a call for anyone to drop their party or organization, but it’s a call for working across partisan lines and perhaps one day creating an institution that can serve as an umbrella assembly for the American communist cause. We are stronger together—so what’s stopping us?

In the chart above I have done my best to depict the major socialist parties in the United States and identify their differences and similarities. I recognize that some groups are missing: Socialist Alternative, Freedom Road Socialist Organization, International Marxist Tendency, and Counter Power, just to name a few. As important as these groups are, they are not on the chart because their membership does not compete with the major parties listed. Although they would certainly occupy a place in a hypothetical assembly, for simplicity’s sake I have left them out.

So, what can this chart tell us? The easiest way to break it down is to analyze by party.

The Revolutionary Communist Party USA, or RevComs, are a neo-Maoist party that utilizes the cult of personality strategy to build the party base around a singular ideology embodied by the individual (in this case Bob Avakian). To be sure, the personality cult is still a form of democratic centralism, although less democratic than the CPUSA or DSA. Curiously, in recent years it has endorsed Joe Biden as the Presidential nominee as a safe alternative to Trumpism. The party’s funding mechanism remains obscure.

The Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL) is likewise a Marxist-Leninist party that takes the hard line of abstaining from voting for establishment candidates. It is a vanguard party, where the source of legitimacy resides in the cult of the intellectual. It is the vanguard’s role, specially endowed with knowledge through the study of canonical texts, to preach class struggle and consciousness to the workers. The PSL has come under fire multiple times for dismissing inter-chapter infractions, co-opting other movements, and promoting a form of elitism. It appears on the chart below the RevComs because its adherence to Brian Becker borders the cult of personality, although not on the same level as the RevComs and Bob Avakian. The PSL is extremely sectarian, and although it operates through A.N.S.W.E.R. coalition, it has repeatedly worked to keep radical voices other than their own from its rallies.

The last two parties—Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) and the DSA are under the cult of the party category. Both parties trace their lineage through the history of American socialism. In the case of CPUSA, the party claims to be heir to the 3rd International’s Communist Unity Party. Although the CPUSA does not typically run candidates, it does not explicitly endorse Democratic Party candidates either. Instead, it has maintained a United Front Strategy since the Second World War and through the red scare, opting to vote for the least fascistic candidate (which most often happens to be blue). The party’s seniority means that it is plagued by the same gerontocracy that weighs down American politics more broadly: its high leadership remains those forged in the struggles of the 1970s and 1980s while the rank-in-file tend to be younger activists. The party is funded by membership dues, although the allocation of those dues remains obscure.

Finally, the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) also suffer from the cult of the party, but for a different reason. Although it can claim its heritage to be the Socialist Party of America, the cult of the party derives more from its faith in numbers: it is the largest socialist party in the country, and thus locates its mandate there. The large numbers came mostly from the political awakening of many Americans following the Bernie Sanders campaign of 2016. The problem with the DSA, as many see it, is that it is the least radical party. Although its membership is mixed—everywhere from anarchists to Bernsteinian radical liberals—the national party is openly reformist. The DSA’s electoral position has been to run candidates through the Democratic Party where necessary and to run its own candidates where possible. The DSA is funded by membership dues.

The differences that I have encountered from comrades across party lines concerned disagreements in platform, strategy, and electoral position. Although we should of course take these differences seriously—as they are a reflection of personal convictions—as communists in active struggle we should not let them overshadow the similarities, which are far more pressing and present. All of this suggests that the unwillingness to work across party lines stems not from any deep-seated disagreement, but from good old-fashioned American ego. Whether operating on a national scale through the personality differences of Avakian, Becker, Sims, or Sanders, or through a more localized scale of personal animosity and distrust, egoism continues to set the conditions of, and grant access to, struggle in American communist organizing.

This reality becomes really apparent when one considers the way in which many engage in polemics. Nothing has brought this out better than the ongoing genocide of Palestinians at the hands of an American-backed Israeli government. While all parties agree that Israel is a settler colonial state, that the United States should withdraw its support for Israel, and that Palestinians deserve liberation and self-determination, many Jewish comrades have come under fire simply for calling for caution when flippantly using words like “zionist.” For example, when I asked about negative experiences in their party organizations, one comrade sent this to me:

“It’s really f**ked up seeing some of the blatant antisemitism from the left. Which I never thought existed. I have been dismissed and had my words twisted and treated like a Jew defending Israel, when I have not once defended Israel. Just for saying we shouldn’t be glib about the slaughter of children, and we should be careful about using loaded terms like “Zionist media” or “Zionist propaganda” as that gets close to dog whistle terms about Jews controlling the media. The left does not need these things to make our case. And I have been told that I’m wrong for feeling marginalized by non-Jews when I call out blatant antisemitism.”

The ways in which positionality is contorted into perceived personal conviction by the receiver, and then polemicized as a personal attack, is endemic in American communism. Rather than accepting personal criticism and engaging with it from the point of self-reflection, it is internalized as personal criticism, and spit back out into the face of the concerned party member.

Another illustrating example showcases how misunderstandings of party structure and platform become entrenched in personal animosity. This exchange, between a DSA and CPUSA member is long but illustrative:

Person DSA: Didn’t ya’ll endorse Joe Biden?

Person CPUSA: No, CPUSA never endorsed Biden.

DSA: I find it funny that yall tout yourselves as radicals considering your only political project is begging dems to the left. CPUSA I’m pretty sure endorsed Biden. (They send an article about the RevComs endorsing Biden, clearly mixing the two parties up)

CPUSA: The RevComs are not CPUSA.

DSA: And the popular front is a liberal strategy. Meaning ya’ll will fold into the democratic party to stop fascism while democrats actively help the fascists.

CPUSA: We will do what is necessary to stop the growth of fascism, that is correct.

DSA: If you think supporting corrupt dems stops fascism, you haven’t been paying attention. Did u forget a big reason we got Trump is because the dem party chose to elevate him as they thought he’d be easier to defeat?

CPUSA: Of course the Democratic Party is a nefarious institution. But the bulk of anti-fascist work doesn’t happen on the national level before it happens on the local level.

DSA: The popular front strategy is not about working with allies. It’s about working with greedy liberals who will oppose you 100% of the way. The dems are literally working with the right-wing against progressive challengers.

CPUSA: CPUSA does not work with “greedy liberals” we work with candidates we deem to be the most progressive and anti-right.

DSA: Ya’ll defend liberals consistently and yes your popular front strategy is 2 the right of the DSA.

CPUSA: We don’t get caught up in meetings about who is more woke and authentically working class.

DSA: You should worry about who is actually working class if your project is supposedly for the working class.

CPUSA: What part of Marxism ever said that the working class has a monopoly on revolutionary work or activity? That’s identity politics. That lib shit has poisoned your mind.

DSA: Ha, I’m not trying to come off as aggressive but I’m just highly suspicious of liberal ideology painting itself as radical politics of the working class. No offense. And I don’t respect a viewpoint that views working class status as a surface level identity. Honestly, I just view your ideas as being at home with radlib politics. Even down to your dismissal of the working-class experience. It’s typical of over-educated folks on the left.

CPUSA: I never dismissed working class experience, but I don’t think measuring poverty is a litmus test for involvement in radical politics, otherwise most DSA wouldn’t qualify. You base your politics off of a working class background, which is crass reductionism and the worst form of reactionary opportunism.

DSA: And again you proclaiming I don’t understand radical politics is typical of over educated libs. Yall think you know more about politics than actual working class ppl. But you don’t.

CPUSA: Consider for a minute how much of what you say is based simply on identity, on self-interest and reaction. Its undisciplined opportunism, it is literally the definition of “radlib” politics, which weaponizes identity to shame, bully, exclude, and stifle actual substantive debate. And not that it matters much but to you it apparently does, I grew up in a 3rd floor apartment with a household income less than 38k a year. But my class background and personal experience is not a basis on which to form my politics. I realized that long ago. Marxism is not crass class reductionism. Its about the abolition of class society, not its replacement with one for the other.

This transcript, aside from being headache-educing, reveals some of the structural problems with American communism more vividly than most sources. The conversation began from a simple confusion of the CPUSA with the RevComs, but rather than correct the mistake the conversation devolved into first broader party-ideological attacks, and then eventually to personal attacks. Disputes such as this almost never concern the points under “similarities” but always concern strategy, platform, and/or electoral position. When disputes do concern “similarities” they are usually minor interpretive differences that do not affect the outcome. It is easy to see how egos worm their way into extra-factional disputes. Lost in the moment, the two party members engage in aimless polemics, ignoring the fact that in reality, both affiliated parties are anti-imperialist, anti-liberal, and indeed Marxist.

Another final source of contention worth bringing up is the pervasive cult of history which exists to varying degrees across the leftist spectrum and underlays even the disputes mentioned above. It is often the case that Marxists, who are well-read and educated, frequently base their legitimacy and personal reputation on their ability to refer to the sources. In one factional dispute observed on X (formerly Twitter), DSA, PSL, and CPUSA members debated the effectiveness of participating in elections. The DSA member blamed the CPUSA member for belonging to a “revolutionary party” only in name but not in practice. As evidence, they quoted a handful of isolated passages from Lenin’s pre-1917 works concerning Russian Social Democracy’s participation in the Duma. Harkening back to the old Soviet form—where claiming proximity to orthodoxy implied objectivity of approach and disciplined interpretation—the assumption on the part of the DSA member was that Lenin’s 100-year-old take was the final say. Again, a dispute centered around electoral strategy, drawing on the cult of the intellectual, reinforcing factional dispute.

However, this dispute is in some ways more concerning than the others because of the way it alienates comrades from their own security of belonging. If they are proven to be deviating from dogma, then the purity of their Marxism is assumed to be tenuous at best, regardless of how poignantly they apply materialist analysis to current events. The assumption is that if the purity is not there, then neither is the authenticity of Marxist convictions—opportunists, radlibs, anarchists hiding under a communist mask. We are so quick to apply these terms to well-intentioned comrades, because our historical forefathers used them. Yet, unlike in the past where polemics occurred in party papers and in constituted governing bodies, today they occur usually from the comfort of our chair.

Without committing the same error that I am exposing, suffice it to say that Lenin knew, as did Marx, that the condition and form of the struggle would vary according to time and place. If we believe that basic Marxist truism, that fundamental idea expanded on by Lenin and later Stalin, then we have to be willing to open our minds to alternative conditions of possibility. American communism always has and always will look different: we are neither fighting autocracy, the quandaries of state building nor diluting our gospel to align with labor. Instead, we are positioned within the heart of capitalism, against our own imperialist state, diluting ourselves through factional disputes. Factional disputes arise from nothing besides sheer ego and individualism. At the end of the day, the successful strategy is yet unknown in America, and if that is the case then all options are on the table. We can fight about strategy, elections, or platform, or we can do what Zinoviev and the Comintern demanded and recognize the commonality of interpretation that is underscored by our mutual commitment to materialism. The choice is really ours.

What does this all say for the future of American communism? It means that we are in big trouble—potentially. Unlike the climate crisis, in which global warming is here no matter what we do, we have the option of remedying the problem of the American communist ego. Climate activists argue that in order to become real stewards of the environment, we have to re-conceptualize our cultural and economic understanding of nature as a commodity and see it as a finite entity striving for ecological balance. I want to make the same argument for American communism. In order to bring about the future we want to see—a socialist future—we need to re-conceptualize our relationship with each other to one that is less hostile and less derivative of the personality, intellectual, and party cults. We need a fourth category. The cult of solidarity. To do otherwise is to condemn the movement to death because in the age of increasing resource scarcity, gross wealth inequality, and liberal hegemony we literally have no firm ground from which to attach each other.