Why All Activists Should Read Das Kapital

For understanding the social and economic dynamics of our world today

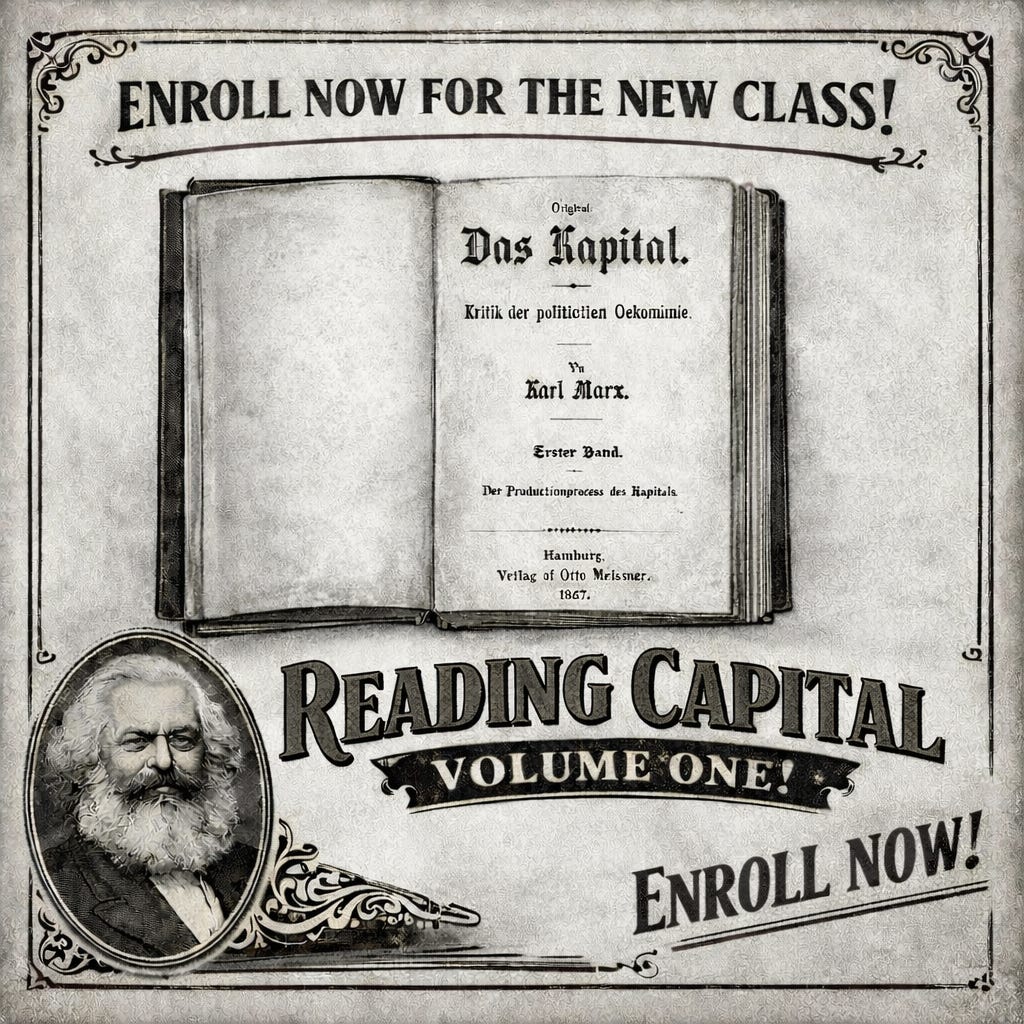

As many of you know, I recently decided that I am ready to lead a 8-week long course on Karl Marx’s Capital, Volume 1. You can find the link to sign up, but in case you need further convincing, here’s a short article about why you should read it. To sign up, follow this link and purchase the post, which will give you access to a google doc with the zoom link, telegram link, and schedule.

If you are confused by any of the following text, a course is the perfect venue to ask questions and become familiar with the common terms associated with Marxism.

Reading Karl Marx’s Capital remains essential for understanding the structure and dynamics of the contemporary global economy and for organizing an effective, grounded critique of capitalism as a compendium to community activism. Capital is not a historical curiosity tied narrowly to nineteenth-century industrial Europe. It is a systematic analysis of how capitalist societies reproduce themselves through exploitation, capital accumulation, crisis, and ideology. Its conceptual framework allows readers to move beyond surface phenomena such as prices, wages, or individual corporate behavior and to grasp the deeper social relations that govern economic life. For activists, this theoretical clarity is not academic luxury, but a practical necessity. Without it, critique risks remaining moralistic, fragmented, or easily absorbed by the system it seeks to challenge.

At the core of Capital is Marx’s insistence that capitalism must be analyzed as a social relation rather than a neutral system of exchange. The global economy today is often described in technical terms: markets, growth rates, supply chains, productivity, and innovation. These descriptions obscure the fact that capitalism organizes human labor and social cooperation in a specific way. Marx begins Capital with the commodity because it is the elementary form of wealth in capitalist society. The commodity is both an object and a social relation mediated through exchange. By unpacking this form, Marx shows how social labor appears as a relation between things, a process he famously describes as commodity fetishism. This insight remains indispensable in a world where global production networks stretch across continents, yet appear to consumers as isolated goods on a shelf or images on a screen.

Understanding commodity fetishism is especially important in the contemporary global economy, where production is geographically fragmented and politically opaque. A smartphone, for example, embodies labor from miners in the Congo, assembly workers in East Asia, software engineers in the United States, and logistics workers worldwide. Market ideology presents this object as the outcome of innovation and consumer choice. Capital teaches readers to see instead a coordinated system of labor extraction organized through capital’s command over production. This perspective allows activists to connect local struggles, such as warehouse labor disputes or housing insecurity, to global processes of accumulation rather than treating them as isolated injustices.

Marx’s labor theory of value, built on Adam Smith’s, is another reason Capital remains vital today. Critics often dismiss it as outdated or purely theoretical. Yet its importance lies not in predicting prices but in revealing the source of profit and exploitation. Marx argues that value arises from socially necessary labor time and that surplus value is generated when workers produce more value than they receive in wages. This concept explains how capital accumulates even when exchanges appear fair. In contemporary capitalism, exploitation is often obscured by service work, financialization, and the language of flexibility or entrepreneurship. Gig workers are framed as independent contractors. Salaried professionals are encouraged to identify with their employers. Capital cuts through these narratives by focusing on the underlying relation between labor and capital, clarifying that exploitation persists regardless of contractual form.

For community activists, this analytical clarity is crucial. Campaigns that focus solely on corporate greed, corrupt politicians, or individual bad actors often fail to produce lasting change because they do not address the structural necessity of exploitation within capitalism. Capital shows that profit is not an ethical deviation but a systemic requirement. Thus, appeals to corporate responsibility or moral reform alone are dead ends. Instead, Capital suggests that the only way to combat this system is by targeting power at the point of production, distribution, and social reproduction, where capital depends directly on collective labor.

Capital also provides a framework for understanding inequality beyond income disparities. Marx demonstrates that capitalism inherently produces class polarization. Accumulation concentrates wealth and power in fewer hands while dispossessing others of independent means of subsistence. This process is visible today in rising wealth inequality, housing crises, precarious employment, and the erosion of public goods. Marx’s analysis of primitive accumulation is especially relevant in a global context marked by land grabs, privatization, debt regimes, and the enclosure of digital commons. These processes are often presented as development or modernization, yet they follow the same logic Marx identified: separating people from the means of life in order to compel wage labor.

For activists working at the community level, this perspective transforms how social problems are understood. Housing insecurity is not merely a result of zoning policy or insufficient supply. It is linked to real estate speculation, financialization, and the treatment of housing as a commodity rather than a social necessity. Environmental degradation is not simply the result of poor regulation but of capital’s drive to externalize costs and expand production endlessly. Capital equips activists with a language to articulate these connections, enabling coalition-building across issues that are often treated separately.

The housing market bubble, the tech bubble, the AI bubble are not new. Capital shows that capitalism is prone to recurring crises due to internal contradictions, particularly the tendency of the rate of profit to fall and the mismatch between production and consumption. While the specific forms of crisis have evolved, the basic pattern remains recognizable. Financial crashes, supply chain breakdowns, and debt crises are not anomalies but expressions of systemic instability. The global financial crisis of 2008 and the economic disruptions following the COVID-19 pandemic illustrate how deeply interconnected and fragile the global economy has become.

For community activists, understanding crisis theory has strategic implications. Crises open political space, but they also generate confusion, fear, and reactionary responses. Without a structural analysis, blame is easily redirected toward migrants, marginalized communities, or abstract market forces. Capital provides tools to explain why crises occur and who benefits from their management. This understanding helps activists intervene with demands that address root causes rather than symptoms, such as advocating for decommodified healthcare, public control over finance, or collective ownership of key industries.

Capital also remains relevant because it foregrounds collective agency. Marx does not present workers as passive victims but as central actors whose labor sustains the system and whose collective action has transformative potential. This emphasis is essential for effective community organizing. Activism grounded only in critique can slide into pessimism or performative resistance. Capital insists that the same processes that produce exploitation also create the conditions for solidarity. Workers share common interests not because of shared identity or morality but because of their position within the production process.

This insight is particularly valuable in diverse, fragmented communities where building unity is challenging. Capital encourages organizers to focus on material conditions and shared dependencies rather than abstract appeals to unity. It also helps activists recognize the limits of individual solutions within a systemic problem. Cooperative projects, mutual aid, and local reforms are important, but Marx’s analysis reminds organizers that such efforts must be connected to broader struggles over power and ownership if they are to endure.

In sum, reading Capital is indispensable for understanding the global economy today because it reveals capitalism as a structured system of social relations, exploitation, and power rather than a collection of neutral market outcomes. It equips readers with concepts that cut through ideological mystification and connect local experiences to global processes. For community activists, this theoretical grounding strengthens critique, sharpens strategy, and sustains collective action. Capital does not offer a blueprint for activism, but it provides something more durable: a method for understanding the world in order to change it.