There’s a powerful line in the song “A Melancholy Boogie” by King Cobra (Infinity Knives and Brian Ennals), recommended to me by a comrade from Rhode Island—Jesse the Tree. The lyric is one that has been repeated in so many words by countless revolutionaries: “You can’t have revolution without no civil war.”

The sentiment echoes the words of historian Arno J. Mayer, who wrote that “The Furies of revolution are fueled above all by the resistance of the forces and ideas opposed to it. This confrontation turns singularly fierce once it becomes clear that revolution entails and promises—or threatens—a thoroughly new beginning or foundation of polity and society.”

I spend a lot of time thinking about the violent implications of my revolutionary politics. As a historian of the Soviet Union and someone who teaches the history of revolutionary thought, capitalism, and climate change, violence in various forms pervades the narratives that I relay to students. As a compassionate person with (I think) an articulate code of ethics, I am in theory a pacifist. Yet there is an extent to which the pacifist, non-violent forms of protest we have been bred to embrace have landed us in today’s destitute subservience to monopoly capitalism, climate catastrophe, and state-sanctioned police militarism. While we refused violence, the State has monopolized it more than ever.

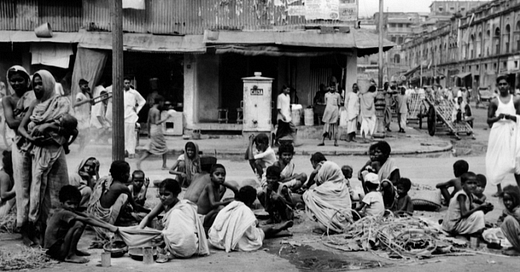

I want to be absolutely clear here with what I mean by violence. I define violence broadly as execution, exploitation, imprisonment, hostage-taking, and intentional intimidation. Such a wide definition captures a plethora of revolutionary movements, but it also importantly implicates existing capitalism. Something that I believe all comrades accept is that the history of capitalism is quantitively more violent than any other world system in history: imperialism, industrial wage slavery, prison industrial complexes, debt peonage, slavery, embargos, economic blockades, racism, prostitution, sexism, and police brutality all qualify as violent acts imposed on people by the exigencies of the system. There is nothing revolutionary about capitalism. The Irish famine, Indian famines, Indigenous genocide, chattel slavery, CIA-backed coups, Opium Wars, and the horrendous acts to protect the “free market” conducted by ExxonMobile in Indonesia and Nestle in China, Brazil, Pakistan, and Ethiopia are just a handful of examples.

Capitalism exercised more specifically through its liberal and neo-liberal forms of exchange, enforced and protected by the bourgeois nation-state, is the most violent system to ever exist. American neo-liberal capitalism has grown increasingly militant, and throughout living memory, the power of America’s military-industrial complex and security forces has grown to gargantuan proportions. The prospect of revolution along the lines of 1917 seems evermore distant and unrealistic in the face of bellicose, well-funded security forces with modern surveillance and precision rockets. Yet, our revolutionary forefathers give us a sense of there being no other option. In The State and Revolution (1918), Lenin is absolutely clear that "The replacement of the bourgeois by the proletarian state is impossible without a violent revolution." Part of this article’s mission is to explore how useful our revolutionary past is when it comes to present conditions. The world has changed, it’s no longer as easy as proclaiming power in Smolny and storming the Winter Palace.

Before diving into this exploration of revolutionary violence, I must state clearly that I am not advocating for violent revolution here. I am merely explicating the historical and theoretical debate that emerged with the Russian Revolution and subsequent revolutionary struggles, lest I be subject to the archaic Smith Act (no doubt another form of anti-communist State violence). My goal here is to interrogate Lenin’s and King Cobra’s line through a historical perspective: is it possible to have a revolution without violence?

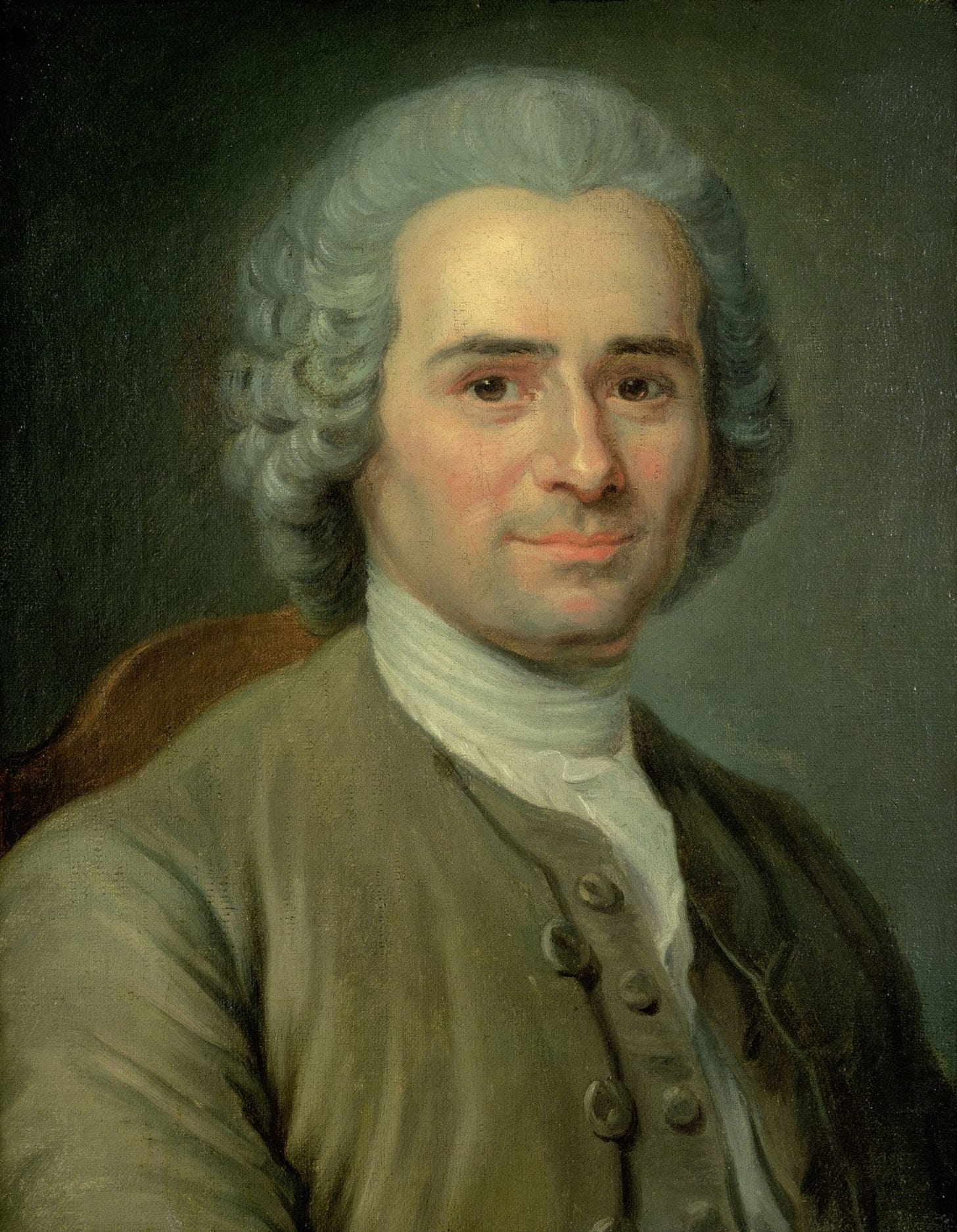

To begin answering the question, we must go back to the European Enlightenment, commonly hailed as the theoretical basis and justification for modern Western liberal democracy. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a Genevan writer and philosopher commonly claimed by liberals as a progenitor of the nation-state, tried to imagine the ideal society and political order based on what he called the ‘general will.’ The ‘general will’ implies that citizens— as a collective nation of individual equals—have a set of desires, standards for governance, and goals, that are embodied and enforced by formally agreed upon laws, and that consent to these laws is a ‘social contract’ that grants access to participation in governing. Rousseau understood that it was nearly impossible to convince everyone to submit to the general will; with any majority, there is always a minority. In Book 1 Chapter VII of The Social Contract, Rousseau explains what is necessary to enforce the general will:

“In order then that the social contract may not be an empty formula, it tacitly includes the undertaking, which alone can give force to the rest, that whoever refuses to obey the general will shall be compelled to do so by the whole body. This means nothing less than that he will be forced to be free; for this is the condition which, by giving each citizen to his country, secures him against all personal dependence. In this lies the key to the working of the political machine; this alone legitimizes civil undertakings, which, without it, would be absurd, tyrannical, and liable to the most frightful abuses.”

It is thus the duty of the majority to bring the minority to heel to ensure the working of the political machine. Rousseau’s idea elicited two predominant interpretations. On the one hand, the early French Revolutionaries believed that national sovereignty (with the nation defined as the citizenry), would create the conditions of consent through participation in the State. At the same time, Rousseau’s idea also indicated a willingness to establish consent through any means necessary.

All of this resided in the realm of theory until the French Revolution of 1789. In its initial stage, the revolutionaries limited the use of force in an official capacity, although the crowds certainly excised their anger on nobles like Bertier de Saucigny and Foulon de Doué. Nobles and aristocrats fled the new republic en masse, unwilling to find out whether the National Assemblymen were willing to turn to violent means to impose the new order. What’s more, being abroad allowed the nobility to court the support of foreign monarchies (in most cases relatives), which they did. By August 14, 1792, the revolutionary regime created the Extraordinary Tribunal to judge suspected and confirmed counter-revolutionaries, and within a month the Convention voted to officially abolish the monarchy. By December King Louis XVI awaited trial and was eventually executed, signaling a violent turn in the revolution.

The execution of the King was a shot heard around the world because it threatened the sanctity of not only the French royal family but European monarchies more generally. In that sense, the revolutionaries deemed the act both necessary and vital to the continuance and defense of the republic. What is more, Louis’ beheading was a warning to the monarchies of Europe: aristocratic prerogative was no longer infallible, and it was this idea that really mobilized the monarchies in Europe against the revolution. Within months of the king’s execution, the regime found itself at war with Britain, Holland, and Spain. Riots broke out throughout France, and counter-revolutionaries organizing from outside Paris seized the opportunity to try to reconquer and impose order. The new regime felt that without defending its gains through force, its hold on power was in jeopardy.

It was at this moment that the most violent phase of the revolution began, with the creation of the Committee of Public Safety and the emergence of Maximillian Robespierre, whose name has become synonymous with revolutionary terror.

Robespierre was a student of the Enlightenment, someone who almost certainly read Rousseau and interpreted the social contract as a legitimate license to use force to fortify the regime. In a passage that seems to pull directly from Rousseau, Robespierre wrote “If the basis of popular government in peacetime is virtue, its basis in the time of revolution is both virtue and terror—virtue without which terror is disastrous, and terror, without which virtue has no power…Terror is merely justice, prompt, severe, and inflexible. It is therefore an emanation of virtue and results from the application of democracy to the most pressing needs of the country.” With that, Robespierre argued that the Jacobins knew what was best for the nation, even if opponents didn’t see it. The ends therefore justified the means.

The use of violence in the French Revolution set the basis of a debate that continued throughout the 19th century. From the Revolutions of 1848 to the Paris Commune of 1871, revolutionaries used violence to defend their interests against a well-organized and well-armed State and conservative counter-revolution. However, it is important to note that in France as in Russia in 1917, State-sanctioned violence did not emerge until after the overthrow of the existing order; the abdication of the tsar like the creation of the National Assembly did not necessitate overt force, although they did require intimidation. In both cases, only the consolidation and defense of the new order necessitated violence.

Relatively peaceful at inception, but violent in maintenance. It is precisely this paradox that further narrows the debate on revolutionary violence: Does the act of overthrowing the old order require violence? How useful is historical precedent? Is violence necessary in a state of expediency? What effect does the use of violence have on the image of revolutionaries abroad? Is violence ethical, and do revolutionaries ascribe to ‘an eye for an eye’?

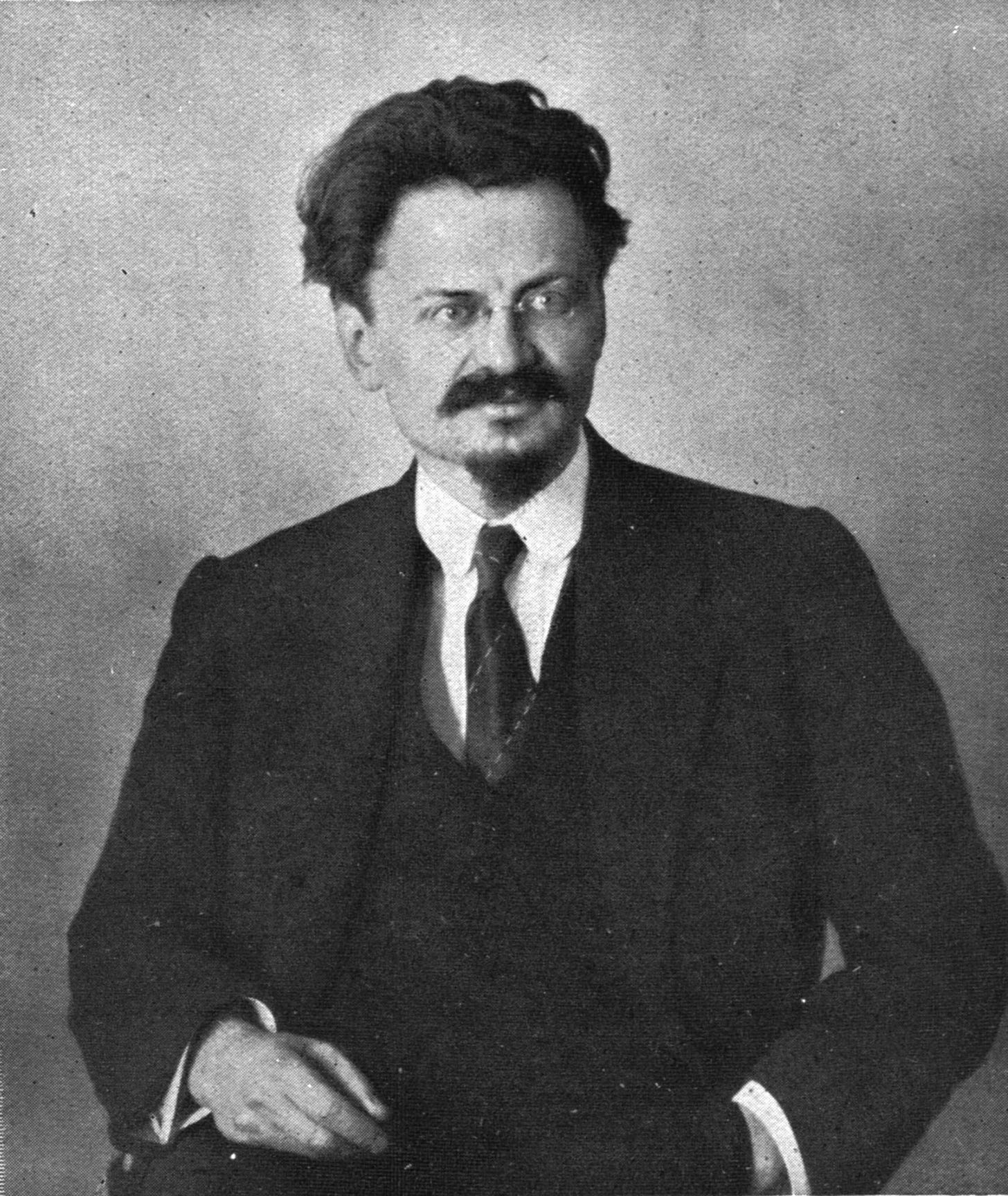

The debate led to a theoretical back-and-forth after 1917 between the leader of the Military Revolutionary Committee and Red Army (Leon Trotsky) and the leading theorist of German Social Democracy (GSDP), Karl Kautsky. As a member of the GSDP, by 1919 Kautsky adopted the party’s official reformist line that suggested socialism could be achieved through the ballot box. For the most part, history seemed to be proving them right. After the failed German revolution of 1918, the GSDP won a majority of votes in the federal elections (37.86%) placing the party at the helm of a coalition government with its moderate leader Philipp Scheidemann as Minister-President.

Considering the relatively peaceful electrical victory of the GSDP, Kautsky exuded confidence and conviction in his assessment of the revolution in Russia. Viewing the developments in Russia from afar, he looked on aghast as the Bolsheviks consolidated power by executing counter-revolutionaries, arresting political dissidents, and exercising extra-judicial punishment for opponents—in complete contrast to the German electoral path. In 1919 Kautsky wrote Terrorism and Communism: A Contribution to the Natural History of Revolution, in which he argued that the Bolshevik use of force signaled not only Russia’s unpreparedness for communism but established a new (negative) precedent for international socialism that overshowed the GSDP’s peaceful victory.

Kautsky’s arguments employed historical examples of legitimate violence in order to undermine the Bolshevik justification for terror.

He argued that if the Bolsheviks viewed themselves as the heirs of the Paris Communards [1871], then we have to remember that the Communards took hostages to protect their own—it was a measure of self-defense, as the bourgeois government in Versailles initially executed revolutionary prisoners. The Communards responded in kind: “There was only one measure adopted by the Commune which can be described as terrorist, and that was the arresting of hostages, undertaken to intimidate the enemy by oppressing the defenseless… the decree [on hostage taking] arose not out of an attempt to destroy human life, but to save it.” Kautsky implies that, unlike the Communards, Bolshevik arrests intended not to save human life, but to destroy political opponents.

In addition to outlining the difference between the Communards and the Bolsheviks, Kautsky expressed a deep anxiety over the consequences that socialist violence had for international communism. He states that “Thiers [the French President] did his best to incite the Commune to slaughter. He knew perfectly well that every hostage shot rendered a service, not to the Commune, but to himself; because it aroused public opinion at large, which was still governed by bourgeois thought and feeling, and coldly accepted the shooting of numberless prisoners at Versailles, whereas it waxed violently indignant over the mere arresting of hostages in Paris.” Kautsky worried that the use of violence in the name of the working-class revolution, broadcasted around the world, would forever taint the credibility and popular image of the socialist movement. He adds that “Bolshevism has, up to the present, triumphed in Russia, but Socialism has already suffered a defeat. We have only to look at the form of society which has developed under the Bolshevik regime, and which was bound to develop, as soon as the Bolshevik method was applied.”

Kautsky’s condemnation of the Bolshevik revolution indited the new worker’s state to the point of obsolescence. He describes violence as a slippery slope, because “even provisionally such a regime could only continue by having some powerful means of violence to support it, such as a blindly obedient and disciplined army.” Once you use violence to impose a new order, it becomes entrenched in the new system and inimical to how it maintains power. For Kautsky, historical examples only go so far, as they are specific to their time and place, and the consequences of force and expediency do not outweigh the risk to international socialism’s reputation.

Leon Trotsky, leader of the Bolshevik defense forces immediately wrote a direct response in Terrorism and Communism: A Reply to Karl Kautsky (1920). Trotsky experienced first-hand the descent of the revolution into counter-revolution and participated directly in leading the Military Revolutionary Committee through October 1917 and the ensuing Civil War. The basis of his defense rests on Marx’s idea of the “dictatorship of the proletariat” where the consolidation of power is a matter of expediency to cement proletarian rule, abolish private property, and seize the means of production. In this, “Only force can be the deciding factor” because, “the man who repudiates terrorism in principle—i.e., repudiates measures of suppression and intimidation towards determined and armed counter-revolution, must reject all idea of the political supremacy of the working class and its revolutionary dictatorship.”

Trotsky’s defense of revolutionary violence rests on the political responsibility of the working class—violence is permissible so long as it is in the name of defense. Thus, the Bolsheviks were merely picking up where the Paris Communards left off, defending their power in a way the Communards couldn’t, “It could, and must be explained that in the civil war we destroyed White Guards in order that they should not destroy the workers. Consequently, our problem is not the destruction of human life, but its preservation. But as we have to struggle for the preservation of human life with arms in our hands, it leads to the destruction of human life.” If the working class is unwilling to use violence to protect their gains, it is doomed to fail. Trotsky essentially argued that some people had to be destroyed in the name of the working class.

This does not mean that Trotsky was some blood-thirsty executioner. He admits that “The revolution ‘logically’ does not demand terrorism, just as ‘logically’ it does not demand an armed insurrection… But the revolution does require of the revolutionary class that it should attain its end by all methods at its disposal—if necessary, by an armed rising: if required by terrorism.” Trotsky’s line of argument here leaves open the possibility of peaceful revolution, espoused by Kautsky and the GSDP, but suggests that it simply wasn’t in the cards for Russia. The centrality of circumstance that Trotsky maintains traces its origins to Marx himself, who in his Address of the Central Committee of the Communist League (1850), states

“As in the past, so in the coming struggle also, the petty bourgeoisie, to a man, will hesitate as long as possible and remain fearful, irresolute and inactive; but when victory is certain it will claim it for itself and will call upon the workers to behave in an orderly fashion, to return to work and to prevent so-called excesses, and it will exclude the proletariat from the fruits of victory. It does not lie within the power of the workers to prevent the petty-bourgeois democrats from doing this; but it does lie within their power to make it as difficult as possible for the petty bourgeoisie to use its power against the armed proletariat, and to dictate such conditions to them that the rule of the bourgeois democrats, from the very first, will carry within it the seeds of its own destruction, and its subsequent displacement by the proletariat will be made considerably easier.”

If self-defense is the fulcrum on which a justification for violence exists, then defense itself has to be defined. The U.N. defines self-defense as “the use of force to repel an attack or imminent threat of attack directed against oneself or others or a legally protected interest.” In the case of the Commune, both Trotsky and Kautsky understood that the communards took hostages to intimidate the government out of executing revolutionaries. During the Russian Revolution, Trotsky pointed out that the arrests, exiles, and executions were necessary to defend the working class from counter-revolution.

Thus, the debate between Kautsky and Trotsky revolved fundamentally around questions of revolutionary expediency and self-defense. Using historical precedent, both polemicists interpreted the past to make their case—nullifying history as an interpretive weapon of justification for the present. As far as the question of expediency, we can only assume that Trotsky, in the throes of revolution, had more license to pronounce what was immediately necessary as conditions arose. Combatants from at least 14 countries attempted to invade Bolshevik Russia, and he was right to point out the emergence of counter-revolution outside of Moscow and Leningrad.

Kautsky, however, was right that the Bolshevik use of violence during the revolution and civil war would cast a negative shadow on international socialism. Not only did objectors such as himself cry injustice at Bolshevik tactics, but liberal critics picked up the criticism and raised it to new heights. Liberal opponents, operating through either the experience of exile and punishment or through the framework of ethics, painted the Bolshevik regime as a violent dictatorship pure and simple. By the time Stalin became General Secretary and implemented terror tactics to enforce unanimity and rule, anti-communist and liberal historians immediately endeavored to draw a straight line from the violent defense of the revolution from 1917 to 1923 to Stalin’s purges and terror in the 1930s. They did not clearly differentiate the forms and causes of violence between the 1930s and the 1920s, and thus branded the entire history of the Soviet Union as Totalitarian, in which an ideology is applied extra judiciously, and homogeneity is inculcated forcefully.

Although we may accept Trotsky’s application of self-defense, there are clear case studies in which the definition is more precarious. For example, Fidel Castro and Che Guevara legitimated the use of guerrilla warfare to protect and liberate the people of Cuba from the dictatorial policies of Fulgencio Batista and American capitalism. More tenuously, Pol Pot legitimated the use of violence under the banner of ‘communism’ in the Khmer Rouge as a defense of ethnic Cambodians. The two examples are obviously far from comparable, but they do reveal the problems with claiming self-defense; who determines what constitutes self-defense? At what point does self-defense lose its defensiveness and become sheer violence? The answer to that, as my students pointed out, depends entirely on the circumstance. However, if force is exacted on ethnic grounds, it is neither communistic nor legitimate.

Violence serves a purpose in revolution, and no example is stronger than that of the Black Panther Party. The Panthers were students of history; they understood that revolutionary violence had to be framed within self-defense and they crafted their ten-point program around the concept of defending black lives and liberty. Although they had a legitimate claim to self-defense, their opportunity for revolution never came. In fact, the State responded in ways that Trotsky could have predicted; members were assassinated and blacklisted at the hands of State agents and political opponents.

The point I want to make here is that revolutionary violence is necessary from a point of self-defense, but ‘defense’ is broadly conceived, and often misappropriated. Take, for example, the conspiracies of those who rioted in the capital on January 6th, 2021, who believed their act was in defense of the ‘rightful’ President Donald Trump. That implies that our revolutionary rhetoric needs to be historically, quantitively, and demonstrably disciplined, leaving no room for doubt.

So where does that leave us today? Well again it depends on how we define our own oppression—are we subject to extra-judicial violence? Does it seem like the ruling class, protected by the State, employs violence to maintain its own order? If yes, then according to our revolutionary forefathers, we are entitled to self-defense by any means necessary. If the answer is not quite, then revolutionaries can’t risk the use of undisciplined and undirected violence, least it gives birth to something far worse.

So that leads me back to the King Cobra lyrics: is it possible to have a Revolution without a Civil War? In his own time, Kautsky would have argued absolutely, although he could not have foreseen the violence that emerged from the GSDP victory. In so far as revolutionary moments also give rise to a reaction, civil war does seem imminent: an individual stripped of their wealth and privilege is likely to spend the rest of their life trying to regain that wealth and privilege. While we may accept the inevitability of counter-revolution, we need to be careful to not glorify violence. Self-defense is not something one should want to exercise, but rather something someone is led to exercise. So maybe it is true that you can’t have a revolution, without being prepared for civil war.